Chapter 1 of 7 in the DesignWare history thread.

Chapter 1 of 7 in the DesignWare history thread.

In thinking back about how I came to the decision to form DesignWare, I have to acknowledge some important roots. When I’m coaching people these days, I always ask them to describe for me their core capabilities — those capabilities or interests that keep coming back into their lives.

My own core is a curiosity about how things work, and a desire to build things of my own. There’s a secondary interest I have in understanding how people communicate and in facilitating communication, and it’s important, but definitely secondary. My early life was in the 1950s, when the pervasive feeling in the United States was one of optimism and growth. I lived in a small town of 1,100 residents. I realized yesterday that large aircraft today routinely carry (each) almost half the population of that town across huge intercontinental distances. My class of 100 fellow high school graduates would just make a dent in the back of the plane.

So my core of curiosity led me to a National High School Institute summer program for high school students, in the summer of 1963, at Northwestern University [NU]. Sponsored by the National Science Foundation, we had some weeks of time on campus in introductory courses, getting interested in science and engineering. One fundamental course was in computing—in which we got access to the card punch machines and instruction on how to write small iterative programs in Fortran. Many years later, my neighbor here in San Francisco was John Backus “inventor of Fortran” — but I knew him more as the father of Backus Normal Form or Backus-Nauer Form which was even more important in my education. The university computer was an IBM 709 — a tube-computer — at our beck and call that whole time. At that time the university didn’t have computers of any size in administration — they were only for research. I learned basic programming, and invented algorithms to do things like shuffle a deck of cards efficiently, and figured out a lot about how probability worked. And programming. I became intrigued by how computer languages worked and what the different languages were good for.

So my core of curiosity led me to a National High School Institute summer program for high school students, in the summer of 1963, at Northwestern University [NU]. Sponsored by the National Science Foundation, we had some weeks of time on campus in introductory courses, getting interested in science and engineering. One fundamental course was in computing—in which we got access to the card punch machines and instruction on how to write small iterative programs in Fortran. Many years later, my neighbor here in San Francisco was John Backus “inventor of Fortran” — but I knew him more as the father of Backus Normal Form or Backus-Nauer Form which was even more important in my education. The university computer was an IBM 709 — a tube-computer — at our beck and call that whole time. At that time the university didn’t have computers of any size in administration — they were only for research. I learned basic programming, and invented algorithms to do things like shuffle a deck of cards efficiently, and figured out a lot about how probability worked. And programming. I became intrigued by how computer languages worked and what the different languages were good for.

I had maybe been destined to become a concert pianist. (A struggling one, at that.) But only until this time when I was sucked into computing. Why computing? It fit my core definition of being something fascinating to understand, and also to be “infinitely tractable” as Alan Kay would later say. A medium in which practically anything you could envision could be simulated, calculated, analyzed, constructed, dissected. Or even better, you could work out alternative formulations of a problem and solutions, both as simulated possibilities and as virtual logical systems making their own decisions.

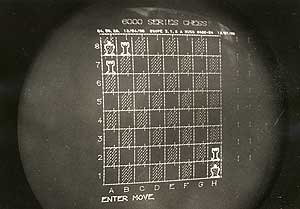

By the time I was in grad school, the university had grown through a CDC 3400 computer to a big CDC 6400. When the 6400 came on the scene, I became part of a varied crew of students who were permitted by the computing center director, Ben Mittman, to use the computer after the midnight shift completed. In those days, programmers punched cards and submitted hundreds or thousands of cards in “decks” to a clerk who then ran them into the computer. Each job would run until completion or abnormal termination, and batches of jobs would run until the shift was completed. On some nights, there might be very few jobs, and even those might terminate abnormally, or just finish early. And we then had the run of the computer until 6am when maintenance work began each morning. In some sense you could consider this “my own little supercomputer” that I had the privilege of using on an unpredictable basis at truly weird hours. I got used to having a personal computer  quite early in my career. A number of important, and some famous, projects were started in this way. Larry Atkin and Keith Gorlen wrote the CHESS 1.0 program in this environment while I was doing my own work in 3D graphics. David Slate joined the team early in that process. I remember vividly more than one time when my work failed, taking down the computer and consequently abruptly ending a session in which CHESS had been playing against itself to learn the game better.

quite early in my career. A number of important, and some famous, projects were started in this way. Larry Atkin and Keith Gorlen wrote the CHESS 1.0 program in this environment while I was doing my own work in 3D graphics. David Slate joined the team early in that process. I remember vividly more than one time when my work failed, taking down the computer and consequently abruptly ending a session in which CHESS had been playing against itself to learn the game better.

To get ahead of my story, my responsibilities in 1969 were to maintain and expand the online capabilities of our computer. This included the systems that allowed CHESS 1.0 to play games through remote terminals, thus freeing the team from having to sit in the computer room to type in or be told the computer’s moves. Development of CHESS continued beyond my own time at Northwestern.

[Read what comes next…] [Or return to the start of the story]

Leave a Reply