Chapter 7 of 7 in the DesignWare history thread.

In late 1984, MSA announced it would divest or shut down Peachtree Software, as well as DesignWare, Eduware and Blue Chip Software. The announcement was made 38 days after the acquisition of DesignWare. Our consumer advertising said “One Tough Speller.” Well we were one tough something-or-other to survive all of this.

In that initial acquisition by MSA, our investors came out OK. I think one investor lost a small amount, and most of them did as well in this investment as they would have in the stock market at that time. Pat McGovern, Chairman of IDG Group, had invested in DesignWare early that year in a last round, and several times after all this transpired, he reminded me that we had done a good job preserving not only their investment, but that of the others. I was relieved, more than happy. In those days it was said that maybe 1 in 10 venture investments might come out very well, with the majority of them fading to zero, and the others just kind of piddling along.

Some time around then MSA started pulling in EduWare and Blue Chip under DesignWare management. I felt terrible about all the laid-off people in those companies. Visited their offices and helped pack up ring binders full of development materials to take back for safekeeping. Nobody would ever look at those again. For years we had surplus ring binders everywhere. But the products still ran and with minor upgrades we could keep them on shelves, adding to the revenues of the combined group. But we couldn’t really spend much, pending MSA taking some final action. So we held our collective breath and worked hard to keep it all alive.

Dennis Vohs, Executive VP of MSA (see link to article above), was looking for a deal to sell these small software companies in some advantageous way. Dennis and I talked to a couple of potential buyers, and really only one of them seemed interested in buying the operating companies (i.e. not just the software titles). This seemed entirely noble on his part—wanting to keep the companies operating—and I was impressed and absolutely willing to get actively involved in selling not only my company, but the two others.

We had great new products. Recognized titles. New fantastic concepts. We had a great reputation. Brilliant new packaging. Really good advertising and great distribution. The market sucked. Let me say that again. Well at least it was pretty bad at that time. You had to keep pushing new flashy titles, and you had to grease the skids with money so stores would put your products up front near the check stand. You had to pay the telemarketers to push your product with the dealers. It was a money sink. And a sale to a big chain was often a loss-leader, meaning we paid more to get the product out there than we reclaimed from actual sales. Damaged products came back for full credit. Lost products never came back, but we had to give credit for them. A tough business. Kind of like the toy business or consumer electronics, you might think? Yup. And the same people. Just be aware. Far cry from university computing, isn’t it?

We had great new products. Recognized titles. New fantastic concepts. We had a great reputation. Brilliant new packaging. Really good advertising and great distribution. The market sucked. Let me say that again. Well at least it was pretty bad at that time. You had to keep pushing new flashy titles, and you had to grease the skids with money so stores would put your products up front near the check stand. You had to pay the telemarketers to push your product with the dealers. It was a money sink. And a sale to a big chain was often a loss-leader, meaning we paid more to get the product out there than we reclaimed from actual sales. Damaged products came back for full credit. Lost products never came back, but we had to give credit for them. A tough business. Kind of like the toy business or consumer electronics, you might think? Yup. And the same people. Just be aware. Far cry from university computing, isn’t it?

Encyclopaedia Britannica enters the scene

MSA had shopped the deal around. Shown it to a number of potential buyers. The only one with real interest was Encyclopedia Britannica, Inc. So we were visited by Patricia Wier and Stanley Frank. Dr. Stanley Frank had been Group President-Publishing at CBS (a group of CBS-owned companies). I hadn’t met him before, but knew the group, as we had done business with a couple of its companies. Initially Britannica said “We’ll pass.” Or that’s what Dennis reported to me. After another round of pushing the pencil, adding the figures, and deciding how to account for the deal, Britannica made a deal, and some weeks we became part of a 400-year old company. He was another of these businessmen that I took a liking to. He was soft spoken, and clearly master of the detail, and well-connected even in our field. Before the completion of this acquisition we had pretty well merged the operations of the three product lines here in San Francisco.

It was still a struggle to find ways to compete in the market and develop new titles. There were a number of good solid companies now in the field. We think the Britannica name was helpful, but distribution was through retail channels, where Britannica had no experience. We coalesced, we continued developing titles, but increasingly were dependent on hit titles. By 1986 I decided to try my computer science expertise in other ways. My personal interest has always been in the building of the company, not in the fine-tuning and “trimming the sail” that has to take place when maneuvering for market share or negotiating manufacturing contracts.

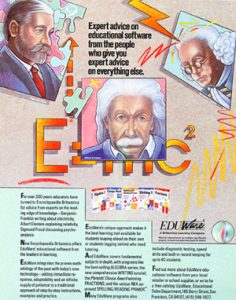

We loved our Britannica image. Our beautiful new ad for EduWare shouted “Expert advice on educational software from the people who give you expert advice on everything else.” — that is, of course, Encyclopedia Britannica — featuring Freud, Einstein, Ben Franklin. Gave us credibility, maybe. Yeah, it probably helped. It also helped that we had resurrected EduWare, which had a good reputation but lacked distribution at retail. (They were big with computer stores and schools.)

We loved our Britannica image. Our beautiful new ad for EduWare shouted “Expert advice on educational software from the people who give you expert advice on everything else.” — that is, of course, Encyclopedia Britannica — featuring Freud, Einstein, Ben Franklin. Gave us credibility, maybe. Yeah, it probably helped. It also helped that we had resurrected EduWare, which had a good reputation but lacked distribution at retail. (They were big with computer stores and schools.)

DesignWare continued to operate as part of Britannica Software for quite some years. Moving to a favorite little stand-alone building I had my eye on in South of Market San Francisco. Stan was focusing on building the Compton’s Multimedia Encyclopedia on CD. We had discussed this and it sounded like a good project. In 1982 when we moved DesignWare to the China Basin Building we were one of very, very few software companies anywhere in San Francisco proper. Most of them were down the peninsula. Today you’ll find hundreds of them in our old neighborhood.

What DesignWare brought to the party was some fresh creativity. Some ways of making the computer do things that were in the educational vein while still enough fun that kids would play with them. It grew from my desire to have a broad impact in education, and from my base as a computer scientist. The crew was composed of creative individuals who loved what they did, even though the programming was tough. What we did was new. So it didn’t matter if we had no experience with edutainment, we were inventing it as we moved along. We left a legacy of titles, Spellicopter, FaceMaker, Story Machine. We wrote Computer Discovery, and Apple bought 20,000 sets of Computer Discovery, to distribute to schools, in its first year. We wrote best-sellers under our name, and best-sellers under other names.

Some DesignWare games, in their Atari incarnations, can be played online even today. If you try them, realize that their simulated speed today is probably about what it was in the 1980s. Back then you would have played using the keyboard and maybe a joystick, and not likely a mouse. Disk access would have been slow. Displays would have been fuzzy. Try to have fun!

One of the more enjoyable moments in my life came around 2014 when I was in conversation with someone who said “Oh, you developed Spellicopter, didn’t you? I used to fight with my brother over who would play it next.” What a wonderful legacy.

Leave a Reply